Lice infestations—medically referred to as pediculosis—remain a global public health concern, particularly in vulnerable populations with limited access to hygiene and healthcare. While head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) are most commonly encountered in clinical practice, body lice (Pediculus humanus corporis) are of greater medical significance due to their ability to act as vectors of bacterial pathogens causing systemic illness.

This blog offers a clinical and pathophysiological overview of lice infestations and their association with lice-borne diseases, including epidemic typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever.

Taxonomy and Types of Lice Affecting Humans

| Louse Type | Species | Location | Clinical Relevance |

| Head Lice | Pediculus humanus capitis | Scalp | Highly contagious; not disease vectors |

| Body Lice | Pediculus humanus corporis | Clothing seams; migrate to skin to feed | Vectors of significant infectious diseases |

| Pubic Lice | Pthirus pubis | Pubic and coarse body hair | Sexually transmitted; no known disease transmission |

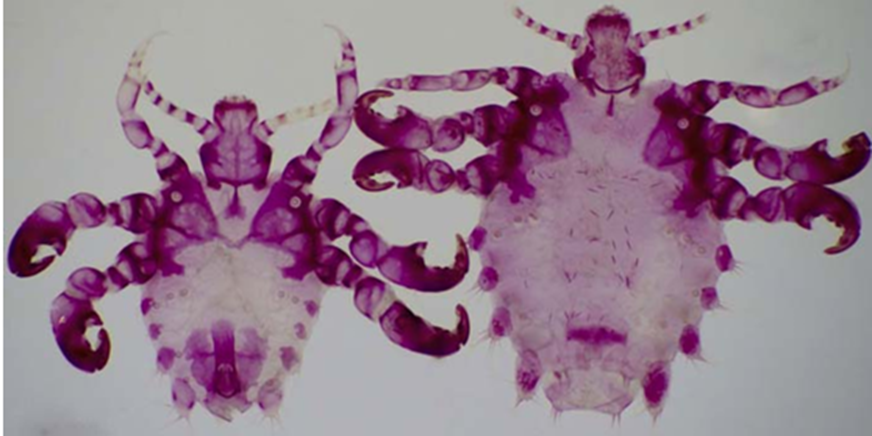

Stained pubis louse with acid fuschin

Epidemiology

- Head lice are most common in children aged 3–11 years, with transmission primarily through direct head-to-head contact.

- Body lice infestations are associated with overcrowded, impoverished, or displaced populations, including those in refugee camps, homeless shelters, or war zones.

- Pubic lice transmission is typically via sexual contact; prevalence has declined with increased pubic hair grooming.

Clinical Features of Pediculosis

Head Lice (Pediculosis Capitis)

- Pruritus due to hypersensitivity to louse saliva

- Excoriations, secondary bacterial infection (e.g., Staph aureus, Strep pyogenes)

- Visualization of nits (eggs) on hair shafts near the scalp

Body Lice (Pediculosis Corporis)

- Erythematous papules, excoriations, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, especially along waistline and axillae

- May lead to lichenification with chronic infestation

- Unlike head lice, body lice reside primarily in clothing

- These body lice are vectors for louse borne diseases.

Eggs of body louse on clothings

Pubic Lice (Pthiriasis)

- Intense itching in the genital area

- Bluish macules (maculae ceruleae) due to louse bites

- Often co-infected with other STIs

Lice as Disease Vectors: Clinical Pathogens

Today, the prevalence and importance of all three of these louse-borne diseases are low compared with times when human body lice were an integral part of human lives and before the widespread use of antibiotics starting in the 1940s. However, trench fever has reemerged as an opportunistic disease of immuno compromised individuals, including persons who are pos itive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

A. Epidemic Typhus

- Causative Agent: Rickettsia prowazekii

- Transmission: Feces of infected body lice contaminate bite sites or mucous membranes

- Clinical Presentation:

- Abrupt onset of high fever, chills, severe headache, and myalgias

- Maculopapular rash, typically starting on the trunk

- Can progress to delirium, hypotension, and multi-organ failure if untreated

- Diagnosis: Serology (IFA, ELISA), PCR, or Weil-Felix test (historical)

- Treatment: Doxycycline 100 mg BID for 7–10 days

B. Louse-Borne Relapsing Fever (LBRF)

An ongoing outbreak of louse-borne relapsing fever is occurring in Ethiopia, where 1,000-5,000 cases are typically reported annually accounting for about 95% of the world’s recorded infections. Other smaller foci occur intermittently in other regions such as Burundi, Rwanda, Sudan, Uganda, China, Russia, Central America, and the Peruvian Andes. Localized resurgence of this disease under conditions of warfare or famine is a possibility.

- Causative Agent: Borrelia recurrentis

- Transmission: Crushing infected lice; spirochetes enter through abraded skin

- Clinical Presentation:

- Recurrent febrile episodes separated by afebrile periods (due to antigenic variation). Episodes of fever last 2-12 days, typically followed by periods of 2-8 days without fever, with two to five relapses being most common.

- Accompanied by rigors, hepatosplenomegaly, epistaxis, and jaundice

- Diagnosis: Peripheral blood smear during febrile episode (dark-field microscopy or Giemsa stain)

- Treatment: Single-dose doxycycline; Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction common

C. Trench Fever

B. quintana has recently been reported to infect at least three species of macaques in southeast Asia and a macaque-associated sucking louse, Pedicinus obtusus, suggesting the possibility of an animal (zoonotic) origin for this disease

- Causative Agent: Bartonella quintana

- Transmission: Inoculation via body louse feces

- Clinical Presentation:

- Recurrent fever (5-day cycles), shin bone pain, malaise, and headache

- Can become chronic in immunocompromised individuals (e.g., bacillary angiomatosis in HIV)

- Headaches, profuse sweating, shivering, myalgia, splenomegaly, maculopapular rashes occasionally and nuchal rigidity in some cases.

- Diagnosis: Serology, PCR, or culture (Warthin-Starry stain)

- Treatment: Doxycycline + gentamicin for severe infections

Diagnostic Approach

- Clinical inspection with fine-toothed lice comb

- Wood’s lamp: Nits may fluoresce pale blue

- Dermatoscopy: Enhances visualization of nits vs hair casts

- Microscopy: Confirm presence of live lice or viable nits

- Rule out secondary bacterial superinfection, especially with impetiginized lesions

Treatment Protocols

| Infestation Type | First-line Treatment | Adjunct Measures |

| Head Lice | Topical permethrin 1% lotion | Repeat in 7–10 days; manual nit removal |

| Body Lice | Improve hygiene, hot wash clothing at ≥130°F (54°C) | Insecticide powders if persistent |

| Pubic Lice | Permethrin 1% or pyrethrin with piperonyl butoxide | Treat sexual contacts, screen for STIs |

Note: Oral ivermectin (200 mcg/kg PO, repeated in 7–10 days) is increasingly used for refractory cases or mass treatment campaigns.

Public Health Implications

Body lice are a neglected vector in modern medicine but remain a threat in humanitarian emergencies. Outbreaks of louse-borne infections have occurred in:

- Eastern Africa (Ethiopia, Burundi)

- Refugee camps in the Middle East and Eastern Europe

- Homeless populations in major cities in North America and Europe

Control measures include:

- Mass delousing campaigns

- Hygiene education

- Access to laundering facilities

- Surveillance for febrile illnesses in at-risk populations

Conclusion

Lice infestations are more than a dermatological nuisance—they may serve as reservoirs and vectors of clinically significant bacterial infections, especially in vulnerable populations. Awareness of the types of lice, their diagnostic features, and the diseases they can transmit is critical for prompt recognition and management.

Early treatment and public health interventions can mitigate both individual morbidity and broader outbreaks of louse-borne diseases.

References

- Raoult D, Roux V. The body louse as a vector of reemerging human diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(4):888–911.

- Brouqui P. Arthropod-borne diseases associated with political and social disorder. Annu Rev Entomol. 2011;56:357–374.

- CDC. Parasites – Lice. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice

- WHO. Vector-borne diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases