Fleas, although small ectoparasites, are medically significant vectors capable of transmitting several zoonotic pathogens. Their global distribution, ability to infest both domestic animals and wildlife, and their capacity to bite humans place them at the center of several public health concerns.

This article provides a clinical perspective on key flea-borne diseases, their etiological agents, transmission mechanisms, symptomatology, and control strategies.

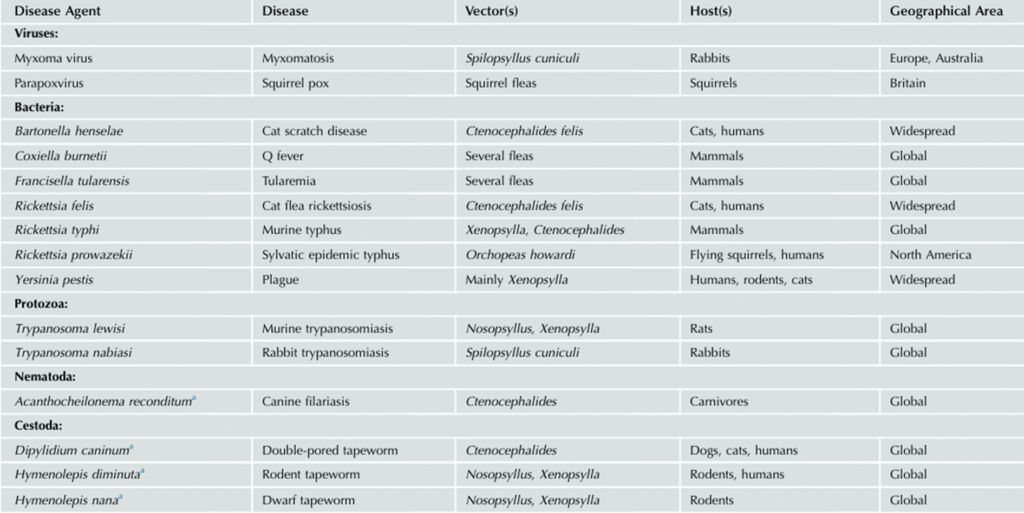

Fleas as Disease Vectors

Fleas (Order: Siphonaptera) are wingless hematophagous insects that parasitize mammals and birds. Over 2,500 species of fleas have been identified, with Ctenocephalides felis (cat flea) and Xenopsylla cheopis (Oriental rat flea) being the most epidemiologically important in disease transmission.

Fleas can act as:

- Biological vectors, where the pathogen multiplies within the flea (e.g., Yersinia pestis).

- Mechanical vectors, transmitting pathogens via contaminated mouthparts or feces.

Major Flea-Borne Diseases of Clinical Concern

1. Plague

- Causative Agent: Yersinia pestis (Gram-negative bacillus)

- Vector: Xenopsylla cheopis (rat flea)

- Reservoirs: Wild rodents (e.g., rats, prairie dogs)

- Transmission: Flea bite; rarely, direct contact with infected tissues or inhalation of aerosols.

- Clinical Forms:

- Bubonic: Most common; characterized by fever, chills, and painful lymphadenopathy (“buboes”).

- Septicemic: Disseminated infection leading to DIC, necrosis, and multiorgan failure.

- Pneumonic: Primary or secondary; highly contagious; acute febrile respiratory illness.

- Diagnosis: Blood or lymph node aspirate culture, PCR, or serology.

- Treatment: Early antibiotic therapy (streptomycin, gentamicin, doxycycline, or ciprofloxacin)

Plague patient with enlarged axillary lymph node, or bubo, characteristic of bubonic plague

2. Murine Typhus (Endemic Typhus)

- Causative Agent: Rickettsia typhi

- Vector: Xenopsylla cheopis, Ctenocephalides felis

- Reservoirs: Rats, opossums, domestic cats

- Transmission: Inoculation of flea feces into bite wounds or mucous membranes

- Clinical Features:

- Incubation: 7–14 days

- Symptoms: Fever, headache, myalgia, rash (often starts on trunk), nausea

- Diagnosis: Indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), PCR

- Treatment: Doxycycline (first-line); chloramphenicol as alternative

Oriental rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis

3. Cat Scratch Disease (CSD)

- Causative Agent: Bartonella henselae

- Vector Role: Fleas transmit the pathogen between cats; humans acquire infection via cat scratches or bites, not flea bites directly.

- Reservoirs: Domestic cats (particularly kittens)

- Clinical Presentation:

- Regional lymphadenopathy (1–3 weeks post-exposure)

- Fever, malaise, papule or pustule at inoculation site

- In immunocompromised individuals: bacillary angiomatosis, peliosis hepatis

- Diagnosis: Serology (IFA/ELISA), PCR, Warthin-Starry stain (histopathology)

- Treatment: Often self-limited; azithromycin or doxycycline in moderate-severe cases

Eggs (ova) and dried blood-rich feces (“flea dirt”) excreted and provisioned as larval food by adults of the cat flea (Cteno cephalides felis)

Cocoons of the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis)

4. Flea-Borne Spotted Fever (Rickettsiosis)

- Causative Agent: Rickettsia felis

- Vector: Ctenocephalides felis

- Reservoirs: Cats, opossums, rodents

- Clinical Presentation:

- Fever, headache, rash (maculopapular), myalgia

- May mimic dengue, murine typhus, or other febrile illnesses

- Diagnosis: PCR, serological testing

- Treatment: Doxycycline

Diagnostic Considerations

Flea-borne diseases often present with non-specific flu-like symptoms, leading to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis, particularly in endemic areas. Key diagnostic tools include:

- PCR for direct pathogen detection

- Serology (IFA, ELISA)

- Culture (in select cases)

- Histopathological examination (e.g., CSD)

Differential diagnoses should include viral exanthems, dengue, typhoid, leptospirosis, and other rickettsial infections.

Prevention and Public Health Control

For Humans:

- Use insect repellents (DEET, permethrin-treated clothing)

- Avoid contact with wild rodents and feral animals

- Maintain personal hygiene and environmental sanitation

For Pets:

- Routine flea control regimens (e.g., fipronil, fluralaner, selamectin)

- Regular veterinary check-ups

- Avoid allowing pets to roam unsupervised in flea-infested environments

Environmental Control:

- Rodent control measures in urban and peri-urban settings

- Flea population management (indoor/outdoor insecticides, vacuuming, washing pet bedding)

- Public awareness in endemic areas

Epidemiological Note

Although some flea-borne diseases, such as plague, are now rare in developed countries, localized outbreaks still occur — particularly in parts of Africa, Asia, and the southwestern United States. Climate change, urbanization, and global travel may contribute to shifts in vector habitats and disease emergence.

Conclusion

Flea-borne diseases, though often neglected, represent a clinically significant group of zoonotic infections. Prompt recognition, early antibiotic therapy, and preventive strategies — especially among pet owners, veterinarians, and healthcare providers — are critical for minimizing morbidity and potential outbreaks.